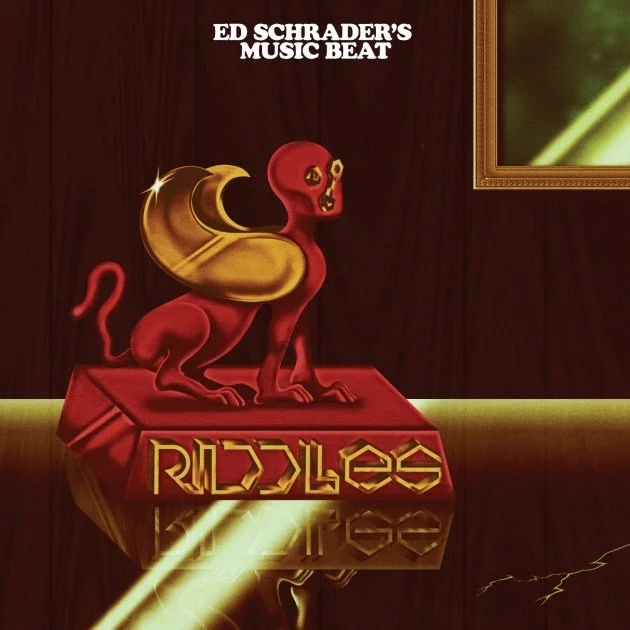

Approaching Valhalla: Ed Schrader and the Dizzy Devil

This month’s Rewind looks at the 2018 album by Baltimore duo Ed Schrader’s Music Beat (Ed Schrader and Devlin Rice), which was co-written and produced by another Baltimore native, Dan Deacon.

Ed

Schrader’s Music Beat

Riddles

Post-Punk / 2018

Discussing Ed Schrader‘s Music Beat with anyone outside of the most niche listeners of Baltimore-centric art…people is kind of a dead end. Their early work is bizarre to the point of almost being unlistenable, and their live shows—often done at the behest of a larger act whose tour happens to be stopping in the city—are equal parts musical performance and stand-up. But there’s always been something deeper going on; maybe Schrader’s avant-garde techniques and art school training couldn’t force it into people’s minds, but it was there.

In 2009, a then-solo Ed Schrader finally achieved what so many struggling artists could dream of: an actual published work. But The Choir Inside, while a milestone for the singer-songwriter’s career, pushed the limits of song structure. Full of manic screams and hyper-repetitive beats, the album did more to induce panic attacks in listeners than awe.

Fortunately for everyone, Schrader decided to team up with bassist Devlin Rice for 2011’s Jazz Mind and its follow-up, 2014’s Party Jail. The result was a significantly more pop-friendly accessibility that better showcased Schrader’s haunting baritone voice, and the duo’s affinity for neo-noir songwriting that bordered between the post-punk of Television and the classic rock of Zeppelin. With Rice officially joining Music Beat, and the intense (if still minimal) interest in Party Jail, the pair were named “Best Band in Baltimore” by several local outlets.

And thus, we find ourselves back at the start. In late 2017, with Schrader and Rice cashing in their much-deserved Baltimore cred with the city’s most likeable electronic musician, Dan Deacon, who they would hire to engineer, produce, and even co-write much of their next album. And, before we even get into breaking the album down, know now that Deacon’s signature sounds are all over this thing: sweeping synths, distorted vocal loops, and pulsating basslines.

Also…

…BRILLIANCE

The utter perfection of Deacon’s production is evident in the very first song, opener “Dunce.” Rice’s bass pounds away, immediately opening the album at full volume, when a highly-processed loop of Schrader’s voice begins looping, tighter and tighter, more and more distorted, until there’s no distinction between human and machine. And so, here we begin the journey, soon to be dropped into a Schrader signature, a nonsensical mantra that will define the song (“got this miracle in my cereal bowl”). Apart from the drums and the bass, every other sound is Schrader’s voice or breath, distorted or processed or chopped-and-screwed into every other “instrument.” There are enough layers here to make Trent Reznor hire Marie Kondo.

“Seagull” is probably the most puzzling track on the album, beginning again with Rice’s bass, but this time with a more upright jazz feel. The second pass brings beatnik finger snaps, like he and Schrader are lining up to rumble with the Jets and Sharks. Schrader then enters with their signature baritone to deliver one of their deeper sets of lyrics, telling a story where our hero flip-flops between acting like a hedonistic teenager forever, or finally growing up and joining the rat race. When we get to the first chorus, Deacon shows up again, taking a single syllable of Schrader’s voice to create a beat around which the rest of the song will be constructed; then adds drum machine and distorts Rice’s bass. Schrader’s lyrics layer in rounds, coos, and croons, building a whirlwind of sound until the song explodes in excitement for the morale of the story, “no vacation destination.” Leaving childhood means we can finally do “whatever we want,” but can we really? The whirlwind dies as quickly as it started, and we’re left with Schrader’s silky baritone and Rice’s jazzy bass. What goes around comes around.

Title track “Riddles” begins with a flurry of gorgeously recorded pianos, appropriate for what will be the album’s emotional and philosophical core. The pianos continue, but make room in the mix for an angelic droning synth accompanying Schrader’s vocals. After the first verse, an 80’s-road-trip-inspired drum pattern enters to really drive home the theme of letting go. As an aside, both Schrader and Rice experienced deep personal losses between the release of Party Jail and the recording of Riddles: Schrader, their father and stepfather; and Rice, his brother. All that is mentioned here to drive home the deep longing expressed in this song. Sure, it’s fast-paced, and more major-key than most requiems, but that loss is felt just as much through beauty as it is through despair. The chorus, delivered by Schrader, belting as loud as they can before losing fidelity, is truly heartbreaking: “riddles do me little favor / sleep until I slip away.” Why is life so confusing?

The most musically complicated song, “Dizzy Devil,” begins as a low rumble and long patter of toms before Rice’s bass hits a single note, increasing the drone-ish build up. When Schrader enters with a classically nonsensical verse, the drone cuts, hard, to a flurry of percussion layers, bass, distorted samples, and synths. Schrader’s voice is itself run through several effects, giving it a distant, echoing, haunted feeling. As each verse and chorus (the fantastic chant of “devil, devil, devil, devil, devil…”) goes by, more layers are added. This song is pure maximalism: more layers, more speed, more drums, more bells, more synths, more samples, more effects, more, MORE, MORE! The pace is blistering, the sound is all-encompassing. The chants of “Devil! Devil! Devil!” are backed by layer upon layer of additional voices, giving the chorus the effect of a mob, a teeming mass of people shouting for their dark lord. The cries and chants build and build when, finally, the song simply cannot hold more, and the song comes crashing to an end like an unstoppable chain reaction of stumbling and spilling over, until all that’s left is a gaggle of saxophones (when did those get here?) that bring the track to a fittingly chaotic end.

The final track of the first half, “Wave to the Water,” is a brilliant juxtaposition to “Dizzy Devil.” An almost mournful dirge of a ballad that showcases Schrader at their crooning best, drawing comparisons to Chris Isaak. The music, equally juxtaposed, is a simple synth chord progression, as minimal as possible to give Schrader’s voice room to soar. The bare lyricism gives the album (and its listeners) a moment to breath and process and reset. It also showcases what Schrader is capable of when they eschew zaniness for sentimentality: “I chased your ghost so many times / cheap old cartoons and battle shrines / blinded by the broken trinkets / shining in steel like holy, old dimes.” And then, just as quickly as the moment of mindfulness began, it ends…

As expansive as Dan Deacon may have made the new version of Music Beat, Schrader and Rice can still rock out a face-melter. “Rust” is Schrader’s homage to that thing that you just can’t fully experience online: live music. There is just something…”more” about really being there with the musicians and speakers in your face with you. “Rust” encapsulates the rush of all the feelings of crowds and music and excitement and way too much caffeine. The saxophones return, if only briefly, to introduce us to the frenetic blast that is “Rust,” before Rice begins a sprinting bassline, and Schrader begins shouting out, in a literal list, places, venues, other bands, and even radio stations that have had a major influence on Music Beat. The sound, now backed by drums rolling as fast as possible, consistently builds with Schrader’s pitch and mania until

BABY GIMME RUST GIMME RUST TO RUST! BABY GIMME RUST GIMME RUST TO RUST! BABY GIMME RUST GIMME RUST TO RUST TO RUST! BABY GIMME RUST GIMME RUST!!!

…ahem, excuse me. Without hyperbole I can officially say this is the most utterly demented I have ever heard someone shout into a microphone, and dear God in heaven is it the greatest feeling. This chorus is the distillation of everything that’s great about seeing people perform real music right in front of you. I can hear the strobe lights and thrashing in every beat. “Rust” is the explosion of raw emotion that can only be expressed this exact way.

“Kid Radium” maintains “Rust”s breakneck speed, but significantly turns down the violence. A driving rhythm and bass section propel us into Schrader’s verses, giving us a honey-voiced tour of the more unfortunate parts of life in Baltimore for many. The song is an allusion to the many issues to city has, including the pervasive and sadly persistent problem of lead paint in children, and a society that choses to fund prisons more than education. The chorus is backed by a headphone-filling, reverbed Mellotron that has the power of a full orchestra. It is a beautiful decay we witness as Schrader mentions Midway East, Bethesda, Bel Air, and Prince George’s County. “I don’t want to nullify / the thing which delegitimizes the other guy,” they croon, a metaphor for the unproductive discussion surrounding the response to the Freddie Grey protests. The soaring synth melodies doing their best, even though it’s not much, to elevate the ghosts of those lost to a corrupt system.

“Humbucker Blues” is, to my knowledge, the only instrumental track ever released by Ed Schrader’s Music Beat. Much like “Wave to the Water,” it acts as a palate cleanser of sorts, but also as a summary of the previous two songs’ energy and mood. Rice’s bass plays a repetitive single note as a backing, but then another layer adds deep minor chords that build out a musical world. Eventually, a melody appears, and it wordlessly advances the plot of this unspoken story, opening sounds like doors to the wider world beyond our computers and phones. Close your eyes, and you can see it.

The stark, unfiltered piano that starts “Tom” jars you from the trance induced by “Humbucker Blues,” before opening further into a operatic ballad. Schrader has stated that the song is dedicated to both their stepfather and to David Bowie (the “Tom” is a direct reference to “Major Tom” of Bowie’s “Space Oddity”), who had passed the year prior to the recording of Riddles. It is by far their most personal and emotional delivery, filled with references to Bowie’s work and memories of bonding with their stepfather over music. It is intense and sorrowful. The first time we hear Schrader sing “I remember Tom,” is very different from the last, now loaded with the ache of feeling, and the grief of what’s lost. “I am running to him / I feel lost and adored / Are you running through me? / I kind of lost my form.” The end cries into the void as the piano is drowned out by an ever-increasing buzz, overcome with memory.

The closer, “Culebra,” is a fantastic ending to the journey that Riddles leads you on. Written about a visit to Puerto Rico (and the Isle de Culebra for which the song is named), Schrader’s lyrics are fully formed—“we drove out in the morning up from old San Juan / the consulate saluted and we had a little rum / Culebra, a spoken myth / into the trees, over the leaves”—creating the most wonderful mental image of the tranquil island and the laziness of a vacation from the rest of the world. The track begins with the sound of coqui frogs as an island-influenced piano line fades in. Beneath runs Rice’s samba bassline, bringing all the elements of a picturesque travelogue together in song. Schrader’s cries of “Culebra” in the chorus cement what a beautiful and happy time this visit must have been. The song ends as it began, the chirping of the coqui frogs fading out as if from a pleasant memory of a much-deserved respite. It is, in every sense of the word, magical.

I still don’t know what I hope to accomplish with a discussion of this album. Riddles means more to me than a small, independent, nearly unheard-of release normally would. And I’m still not sure how to talk about it, even when I really want to. At times, it’s brick-shittingly unhinged, letting every emotion bubble to the surface and boil over in a hedonistic display; others, it showcases the true beauty that rock music can have. I guess, I just want more people to listen to it. Riddles is a brilliant piece of art, both an ode to music itself, and an elegy to those we lost. It admits to its alienation, and it celebrates togetherness. A gorgeous, sumptuous mess, it is my sincerest hope that Riddles may never be solved.